Catching up on contemporary practices on the ground

- Michael Hornsby

- Jul 23, 2018

- 4 min read

There seems to be a number of unclear objections to the reporting on ‘new’ speaker perceptions of their own place in a minority language setting and the impact other speakers have on them. I am not going to critique them here, but interested readers could refer to recent research I have published in the publications section of this website. The term ‘new speaker’ arose from a number of meetings, conferences and symposia which colleagues held, originally in Scotland, and which was then developed to include a wide range of settings across Europe and beyond. The original intent was to give voice to a section of minority language communities whose voices had otherwise had not been heard or had been downplayed.

Within the New Speaker Network, of which I was an active member between 2014 and 2017, the intent (nor, indeed, the result) was never to dismiss the native speaker perspective/experience, since of course these narratives are at the core of the communities under discussion. And it is my assertion that such speakers were never overlooked in our explorations, since the literature is replete with examples of traditional communities and tradition forms of speech, and this has been the dominant trend in many minority language studies to the present.

The new speaker narrative is also an important one and needs to be taken into account. This is why the concept of ‘new speakerness’ is salient. It is probably the first time these accounts are being taken seriously. Indeed, these narratives need to be heard if we are to consider what the future is for a number of minority languages.

That a number of writers have begun to look at alternative accounts of different types of speaker in minority language communities can be seen as challenging to the ‘orthodox’ view that many of these communities are in some way bitterly divided on the question of 'older' and 'younger' speakers. In Brittany, for example, researchers from the 1980s onwards have written of the gap between young and old, between ‘traditional’ and ‘neo’ Breton and between legitimate and illegitimate speakers. Is this still how people feel, outside of academic circles, though?

Recently, during a visit to Plounéour-Trez, the owner of Café Ty Pikin engaged me in conversation about where we from, etc, and initiated a conversation about Breton. She recounted, as someone brought up with Breton as one of the languages in the home, but unconfident in using it as adult, how accomplished she felt in having finally read an entire book in Breton about her locality. She had had to read the text out loud in order to ‘translate’ it into her own dialect, or, in other words, relate it to how the older generations would have spoken Breton in the past. A recapturing or playing back of their voices, as it were. I asked her about younger people speaking Breton nowadays. She showed a certain sense of pride that there was a Diwan school in the nearby town, and that there were now young people who were able to read Breton much more fluently than she had been given the opportunity to do. I had to ask, since we are repeatedly told that there's a linguistic gap: Are the youngsters in the village who go to the Diwan school understood by the older people? “Of course! There are some subtle differences in the way they speak but yes, it’s still the same language.”

Even though such statements by community members are regularly downplayed, rejecting narratives about new speakers as inaccurate, or untrue, is to project one truth on a situation. There are multiple ‘truths’ in any such case. Foucault, for example, sees all systems of knowledge as discourses, not as ‘truth’ but as ‘regimes of truth’. Is it really the researcher’s place to advocate or defend the stance of certain groups of speakers - who in fact may not actually feel the ‘gap’ of which certain commentators seem so fond? To do so may be perpetuating an academic discourse which, while it undoubtedly intersects with what the woman on the street says about such matters, is in all likelihood self-perpetuating and can be seen in very different terms outside of academia.

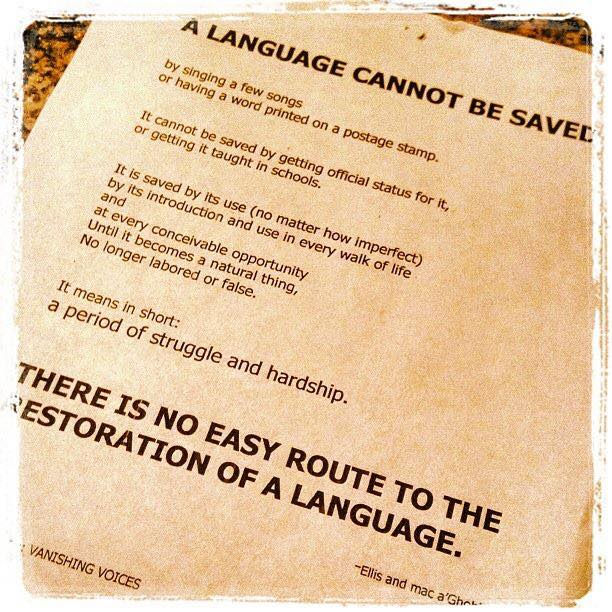

A language is ‘saved by its use (no matter how imperfect)’, as Berresford Ellis and Mac a' Ghobhainn pointed out in 1971. 'Imperfection' is subjective in this case, and very often means a form of language that some person or some group dislikes. The words of the authors still ring true today.

Unfortunately (in my view, anyway), some linguists are unwilling to listen to any account which cannot be quantified and measured according to syntactic rules, or typological frameworks, even when these accounts come from speakers they themselves would view as ‘authentic’ (i.e. brought up speaking the language from childhood). The lack of appreciation for approaches other than their own narrow fields does a disservice for the field of minority language studies as a whole and misrepresents (and indeed distorts) current linguistic practices within many speech communities. A student reading the grammar of a local dialect of Breton, or consulting a corpus of recorded speech of the language (carefully compiled and edited to exclude non-canonical speakers) will, on entering the field, be confronted by a confusing plethora of variation among contemporary speakers and wonder why on earth these variations are not mentioned in the literature. That is why alternative accounts are so important. And these descriptions are most profitably studied by taking a postructuralist approach, which is ‘an attempt by theorists of language to catch up with contemporary practices on the ground, which traditional approaches, based on taken-for-granted structures and modernist understandings of society, are ill-equipped to analyse and explain’ (Kelly-Holmes and Adkinson 2017: 238). These accounts complement and do not replace other, more structuralist descriptions, but together can provide a much fuller picture of what it means to be a speaker of a minority language in the twenty-first century.

Comments